I was recently introduced to the following paper on the Australian fire service, which is an absolute banger. It starts with the following quote.

The basic state of affairs is ignored, to wit, that modern society has no control center.

It's a wonderful piece on ritual and absurdity, against a backdrop of a bunch of people doing their best to save an environment that they love amidst a swirl of panicked politicians, managers, and ground staff, all struggling to balance the fundamental uncontrollable nature of the real world with the various psychological undercurrents that ripple through any large group of people. The thrust of the article is that individuals in these environments perform control, meaning that they do their best to act as if they are exercising top-down control on an unsettling situation, when in reality things like this are happening:

You've got [an analyst] looking at whether to light up this fire break or this fire break, going over the alternatives, weeks and weeks ahead … but meanwhile the ground crew have gone out and lit up the first one and not told us.

I don't have a real job, unlike those absolute units out there fighting Australian bushfires, so I can't relate to the part of this where they actually go out there and fix a problem that they care about. What I can talk about a little bit is this idea of performative rituals, and what I've observed in corporate settings around the rituals that surround a lack of capability. Today's writing is just some reflections on what causes people to flock towards running senseless rituals in offices.

I.

Two ideas are relevant. One, the median professional seems to be reasonably bad at their job. Two, the usage of rituals and affirmation serves to help people cope with uncertainty, anxiety, and identity.

To the first point, what I mean is that when my friends see psychologists for any reason, the average psychologist seems to blunder so terribly within the first session that said friends usually decide not to continue treatment at all. The average non-tech blog reading engineer seems to struggle immensely with operating Git. The average manager seems to very sincerely struggle with how to trust their team to do anything. The average person in almost any complex field is just... well, not very good. Society would look very different if this wasn't the case.

With this lack of clear competence comes a great deal of neurosis. I just had breakfast with an extremely talented clinical neuropsychologist, a very complex healthcare discipline which can involve the nerve-wracking task of advising a surgeon on which bits of a brain to cut out. It is a fascinating area, and absolutely fraught with the kind of messy reality that doctors are plagued with. As my friend put it, "I've had many sleepless nights, waiting to head into the hospital tomorrow to find out if I made the right call and my patient can still talk post-surgery."

However, my friend went on to say that the average practitioner in the field simply refuses to engage with that messy component of the work, and rapidly flees into the safe, dry, high ground of applying psychological testing frameworks to patients, because now the framework is responsible for the final call, not them. From reading a lot of Atul Gawande, and more personally, having a father that is considered a world-class surgeon, this is simply not how one practices high-level medicine. Things are messy and that's what a professional is expected to handle. Even when some complexity leaves the field, it migrates somewhere else. I don't know a damn thing about manual memory management because I studied in the era where Python exists, but am instead asked to consider completely different categories of nonsense, and there is no responsible way to escape that.

Under conditions of both involuntary incompetence and anxiety, driven either by the domain itself or personal inability, it is only natural that many people would be driven to feel better. You can train to become more competent, but you might still be anxious, and this is probably the natural state of affairs. And if you simply don't have what it takes to be better for whatever reason or to even understand what is going wrong, the only reprieve lies in addressing the symptom, the feeling of anxiety, i.e, you begin to construct narratives and rituals to feel like you're being responsible.

II.

Most organizations that I have observed are obsessed with documentation that no one reads and meetings that no one really benefits from. For some time, I thought this was because the people asking for them were under the impression that these things were actually important. That is, they thought that the documentation was enabling us to more effectively keep track of our decisions (despite being an unsearchable and unmaintained morass) and that the meetings were an effective means of communication information (listen, you've seen what most meetings are like).

This is partially true. But actions can serve manifold purposes, and because we're fundamentally monkeys, the underlying current to a lot of actions is simply emotion management. I have come to suspect that many of the managers I work with schedule meetings because it is what they think a responsible person does.

Consider the plight of my current team lead. They are a delightful person, but struggling desperately with not understanding how to manage an engineering team, and even if that wasn't the case, their superiors have made enough mistakes that hitting their delivery goals is essentially impossible. From both a workflow and emotional perspective, they do not understand how disruptive it is to interrupt engineers multiple times a day to ask how specific tasks are going. If they did understand those things, it wouldn't make that much difference at this point, because management is denying engineers raises for saving half a million dollars and giving them $30 gift certificates instead. That'll make someone work just hard enough to not get fired.

The team lead is limited by both his competency as a manager and circumstance. Their understanding of what is going wrong is muddled, but what they do understand is that they are falling behind their commitments to the organization with every sprint, and this is understandably very frustrating. They want to do a good job, but for whatever reason, they lack competence and the ability to handle that frustration gracefully. And listen, I get it, look at how unhinged my blog is. It has been called many things, but "graceful" is not one of them.

The only thing that is immediately apparent to this lead is that for some reason the team only hits half its sprint points every week, which means we fall a little bit further behind our commitments to the organization with every passing week. Things are spiraling, and I suspect that arranging all these meetings and documents feels responsible as the reaction to what feels like a disaster.

That is, the majority of our leadership has never shipped something that unambiguously made money for the organization, let alone enough money to pay their own salaries, and I suspect they don't actually know what it takes to generate $200K in revenue. In the most pathological cases, the average career corporate manager seems to be unable to disentangle real business value from the fabricated kind on their CV. For example, a very common move I've seen is to predict that a project could have cost a million dollars, and when those costs never materialize, say that some work you did is what prevented it from happening. I suspect this is either a non-trivial deception for the CFO to see through, because sometimes preemptive cost-saving is a real thing, or that it isn't worth the political effort to contest these analyses because it would require some sort of technical audit. In any case, some people literally have no experience delivering results that aren't of this entirely fake variety, but also believe what they're saying about their previous performance - it is easier to lie about results than to get results, and it is easier to appear confident when you believe your own lies, and confidence is well-regarded in interviews, so we select for self-deception.

Can you imagine how stressful it would be to try deliver results in a field where you have no idea what the hell you're doing? Like literally no idea? I remember my first day as an engineer, where I was sat in front of a horrendously structured Oracle database and told to try to produce a report. I was well-supported, but I was anxious. I hadn't written any SQL in a real codebase, I didn't understand the domain, I didn't know what information was useful to the stakeholder, and I had no idea how to tell if the dashboard looked good. At least as a fresh engineer, people had patience for me. A lot of our directors never moved beyond that level of understanding, and that is why they're shipping GPT chatbots.

When you've built a whole career out of this, they've got no idea what they're doing, much like the psychologists who drive away their patients during the first session, but they've been told what a responsible manager superficially does. So they do that.

They've heard that modern teams run standups, so they run standups with no ability to judge if it is actually producing the outcomes they want. Huge volumes of documentation are produced, with no intuition or understanding of what documentation would actually be useful to day-to-day operations. While there are no operational improvements from doing all of the above badly, it at least produces the feeling of doing something, and in particular, something a manager is supposed to do, whatever that means.

III.

I haven't prepared a punchy takeaway or useful intervention here. The truth is, I have basically no ability to make these people see what they're doing, as per that old saying around not relying on people to understand things when their income relies on their continued incomprehension. The only thing I can do is determine whether I'm actually being responsible myself, then try to behave accordingly. I have two very simple litmus tests for this.

The first one is whether I'm getting the results I want. If I'm getting good results, I'm probably being responsible.

The more interesting case is when I'm not getting results, and I want to be sure that I'm actually doing my best. My test here, in accordance to the above, is literally whether I'm not doing what everyone else is doing. Doing something weird means I'm actually being responsible.

By way of example, when I graduated, I desperately needed a job in the first world so that I wouldn't have to return to my home country. I had seen a lot of people try and fail to find work, because Australian companies largely just throw your CV out as soon as they see you aren't a permanent resident. This really isn't that big a deal, as a good engineer is worth handling a little bit of visa drama if you want them around when their temporary visa expires in two years, but HR doesn't care about that.

I'd spent a long time watching international students send out application after application, only to get rejected every single time. They would then complain for ages about how discriminatory the country is, so on, so forth. I mean, all fair points, but it was also clear that they were simply applying so that it wasn't their fault they couldn't find work. They did what they were supposed to, right? I got my first job in 24 hours, starting at about AUD 100,000, and frankly not actually being a very good engineer - I was still in the can't-use-Git phase of my career, thank you academia!

How? I bypassed HR. I started digging up the names of the most senior engineer (someone who would suffer from an incompetent hire), cold contacting them, and talking about the job before applying. This was enough to get me interviews, and took me about a day.

Of course, the typical person turns up to an interview and wings it, especially as a fresh graduate. I hired a professional interview coach for two hours at the recommendation of a family member, and I have absolutely dominated the competition in every interview I've sat since then, at least on the behavioral components. It was weird, but it worked. Hell, here's the coach, buy this for your kids when they graduate. Nothing revolutionary to an industry veteran, but this prevents young people from wasting their first few valuable interview opportunities.

This stuff feels weird. I felt like a weirdo sending those cold contacts out into the world - couldn't I just send CVs comfortably into the void? It felt even weirder spending like $300 for an hour of interview practice, even though it was super obvious. At an Australian engineer's salary, the interview would only have to save me one day of job searching to be a net positive. Is there any universe where a graduate wouldn't benefit from even mediocre interview preparation?

I just trusted my model of the world and took action, and it turns out that in many domains, that action is weird. People ask me all the time how I do anomalously well in some domains (you'll just have to trust that I'm not being an immodest jerk here), and I link them to the resources I use, and then they proceed to not read or do any of them, because actually reading on salary negotiation or psychology is unusual.

I take it back, I do have a punchy takeaway. Being weird is a sign of life.

Always reblog

As a former zookeeper we would hear this a lot. “If you don’t study hard you’ll end up cleaning poop for a living.” It’s the one time we’re allowed to go off on the visitors. I once heard my boss rant for five minutes at a lady, in front of her kids, about how he had a Master’s degree, how people literally worked there for free, and how dare she judge people without bothering to know anything about them. Later that day his boss came by and said, roughly, “She told us what happened. Thanks for not throwing anything this time.”

I can count on one hand the amount of times I have gone off on people, but employment snobbery gives me the rage. I was showing the new kid how to use the fry scoop at McDonald’s “.. like this, and then just sort of hold it perpendicular and give it one tap..”

And the new kid sniggered “isn’t perpendicular a bit of a big word for McDonald’s?”

Something in me was just so annoyed by this 16yr old who was learning to work right next to me and somehow felt above us? Fuck that shit. I pointed at the people just on the floor and went off, “she’s a 4th year law student, she’s the primary career for her terminally ill daughter, he raises 100,000 for charity every year, she manages 3 stores and more than £16mil in turnover a year. What the fuck do you do?”

He just sort of mumbled “I didn’t know”

“you shouldn’t have to know, you’re not better than us. So. You tap it once and then move it here to release…”

“I didn’t know.”

“You shouldn’t have to know,”

yes to all this because workers can be educated and intelligent, but also, even if workers are formally uneducated or dont know big words that doesnt mean they arent equally deserving of respect

Zookeepers bust their asses shoveling shit and feeding apex predators so you can stare at an elephant without flying to Asia or Africa.

Fast food workers bust their asses surrounded by hot ovens and boiling oil so you can get food quickly without having to make it yourself or even learn how.

Janitors bust their asses cleaning up the most vile things humans can do to a public room so you don’t have to tiptoe around human waste everywhere you go.

Mail carriers bust their asses going door to door in near-fatal heat/cold and have to deal with the possibility of getting attacked by your poorly-trained pets so you don’t have to drive to the post office every single day.

Warehouse workers bust their asses making sure YOUR latest Amazon crap doesn’t just disappear into thin air.

And retail workers bust their asses coddling and picking up after you like your parents because none of you know how to read a price tag or stop deliberately miss-shelving things you never wanted.

But sure, go ahead and act like you wouldn’t be dead in a week without these people.

Yesterday, the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association (BCCLA) posted an important collection of 284 documents relating to the operations of the Communications Security Establishment. The documents provide a unique window into the ways the statutory provisions governing CSE were interpreted and operationalized by the agency in the period between 2001, when CSE's first statutory mandate was added to the National Defence Act, and the 2019 entry into force of the CSE Act. They also provide rare insight into the way CSE's signals intelligence (SIGINT) and information technology security (ITSEC) programs actually work.

In 2013, in the wake of the Snowden revelations, the BCCLA took the government to court, alleging that CSE’s bulk collection of metadata and incidental collection of private communications violated Canadians’ Charter rights to privacy. The case, which went on for several years, took place behind closed doors, and is likely ultimately to have played an important role in the government's decision to enact a number of reforms to CSE's powers and the oversight and review mechanisms for the agency in the CSE Act and other parts of Bill C-59, passed in 2019. (You can read more about the litigation here.)

During the course of the litigation, the BCCLA was provided with a large body of documents concerning CSE's operations. Although heavily redacted in many parts, these documents contained a lot of never previously revealed information about the agency's activities, with particular emphasis on the rules and procedures governing the collection and handling of communications and other information concerning persons located in Canada and Canadians located anywhere by CSE's signals intelligence (SIGINT) and information technology security (ITSEC) programs.

Unfortunately, they were provided under a confidentiality undertaking that prevented the BCCLA from making them public. However, in 2017 I made an access to information request for the documents, and eventually, following an appeal to the Information Commissioner, they were provided to me with no additional redactions. The government then released the BCCLA from its undertaking.

Now the BCCLA has made the collection, comprising over 4,900 pages of documents, available for download on its website. You can find the links at the end of Greg McMullen's guide to their contents.

I've also put together some introductory notes here.

The following key operational policy documents are included in the collection:

OPS-1, Protecting the Privacy of Canadians and Ensuring Legal Compliance in the Conduct of CSEC Activities (AGC 0022)

OPS-1-1, Operational Procedures for the Release of Suppressed Information from SIGINT Reports (AGC 0020) (28 September 2012 version) and OPS-1-1, Policy on Release of Suppressed Information (AGC 0253) (14 November 2014 version)

OPS-1-6, Operational Procedures for Naming and Releasing identities in Cyber Defence Reports (AGC 0011)

OPS-1-7, Operational Procedures for Naming in SIGINT Reports (AGC 0019)

OPS-1-8, Operational Procedures for Policy Compliance Monitoring to Ensure Legal Compliance and the Protection of the Privacy of Canadians (AGC 0024)

OPS-1-10, Operational Procedures for Metadata Analysis [redacted] (AGC 0012)

OPS-1-11, Retention Schedules for SIGINT Data (AGC 0007)

OPS-1-13, Operational Procedures Related to Canadian [redacted] Collection Activities (AGC 0023)

OPS-1-15, Operational Procedures for Cyber Defence Activities Using System Owner Data (AGC 0018)

OPS-1-16, Policy on Metadata Analysis for Foreign Intelligence Purposes (AGC 0279)

OPS-3-1, Operational Procedures for [redacted; probably "Computer Network Exploitation"] Activities (AGC 0026)

OPS-6, Policy on Mistreatment Risk Management (AGC 0266).

These twelve operational policy documents provide the most detailed window into the policies that govern CSE's operations ever made available to the public. It is important to note that all were superseded in 2018 when CSE introduced an entirely rewritten Mission Policy Suite in preparation for the passage of the CSE Act. However, it is likely that most of the details of those policies remain unchanged, so the documents also provide the best currently available insight into the likely parameters of present operational policies at the agency.

The collection also contains numerous other documents, training materials, and briefing decks that provide further insight into CSE policies and activities. These include:

- The Ministerial Directive issued by the Minister of National Defence on CSE use of metadata (both the 9 March 2005 version (AGC 0004) and the 21 November 2011 version (AGC 0017)).

- The Ministerial Directive on the Integrated SIGINT Operational Model (AGC 0076), which governs CSE's relationship with Canadian military SIGINT activities.

- Examples of the annual Ministerial Authorizations issued under the pre-2019 system to authorize CSE collection activities risking the inadvertent collection of Canadian private communications. Examples of the background memos provided to the Minister of National Defence to explain proposed Ministerial Authorizations are also in the collection.

- CSE's classified Annual Reports to the Minister of National Defence for fiscal years 2010-11, 2011-12, 2012-13, and 2013-14.

- Copies of many of the memoranda of understanding between CSE and client departments on the provision of SIGINT services.

- Subsidiary policy and procedure documents on a wide range of subjects, such as Producing Gists for Indications and Warning Purposes (AGC 0134), Targeting Identifiers for [Foreign Intelligence] under Mandate A (AGC 0135), and Foreign Assessments and Protected Entities (AGC 0136).

- Two training manuals for CSE employees: SIGINT 101 Orientation Program (AGC 0182), an introduction to CSE's SIGINT program, and DGI [Director General Intelligence] Familiarization Manual (AGC 0193), an introduction to work as a SIGINT analyst at CSE.

- Numerous classified reports from CSE's pre-2019 watchdog body, the Office of the Communications Security Establishment Commissioner (OCSEC), and CSE's responses to those reports. These include OCSEC's 2015 review of CSE's metadata activities (AGC 0278), which examines a series of failures by CSE to protect information about Canadians in metadata shared with foreign partners. This report is the best source of information available on those events, which led to the only declaration that CSE had failed to comply with the law that OCSEC ever issued.

In addition to broader policy questions, the documents are an unparalleled source of background information about aspects of CSE's activities. For example, one OCSEC review (AGC 0110) describes the nature of the Client Relations Officer (CRO) system that CSE uses to deliver SIGINT products to many of its government clients. Another (AGC 0179) contains the first data ever released to the public on the percentage of requests made by SIGINT clients for Canadian Identity Information that were approved by CSE (1113 of 1119, or more than 99%). In 2021, the National Security and Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA), which replaced OCSEC in 2019, was able to release additional data on CSE's approval rate for requests, possibly in part because the BCCLA release had already established that such data could be declassified.

In other cases the documents provide insight into aspects of CSE's activities that the agency is still redacting from NSIRA reports. For example, pages 19-21 of this NSIRA report released in 2021 discussed a flawed policy related to privacy protection that was later rescinded by CSE, but NSIRA was evidently unable to include any information about the nature of the policy in its report. The key details of the policy in question can be found on pages 30-31 of OPS-1-7, Operational Procedures for Naming in SIGINT Reports (AGC 0019).

In other cases, one can observe the evolution of CSE policies over time. For example, in document AGC 0182 (p. 99) it is explained that "we [CSE] do not have to protect the privacy of non-Canadians in Canada. This means that in reports we can name people who are in Canada and who fall into certain categories like holding work or student visas, or who are illegal immigrants." But document AGC 0206 (p. 122) reports that this policy was changed in April 2014, with CSE's privacy policies now covering all persons in Canada. (Given the timing of this change, it's likely that it was made in response to the BCCLA's legal action.)

The documents are also a gold mine of information on the official definitions of key terms used by CSE, encompassing concepts such as Canadian Privacy-Related Information, Metadata, and Contact Chaining. The BCCLA has put together a guide to many of those terms here (but note that their glossary is "a work in progress and not intended as a formal dictionary").

Some of the documents in the BCCLA collection have previously been released to individual requesters through the Access to Information Act. But in many cases the versions released were significantly more heavily redacted than the versions provided to the BCCLA. (The parts of the documents pertaining to CSE's mandate to provide support to federal law enforcement and security agencies are an exception, however, as those parts were redacted in their entirety from the BCCLA documents as "not relevant" to their case.) In addition, in many cases documents released to individual requesters are never published or otherwise made accessible to other researchers or the general public.

The BCCLA collection is unique in providing systematic access to these documents for online research and downloading.

Enjoy!

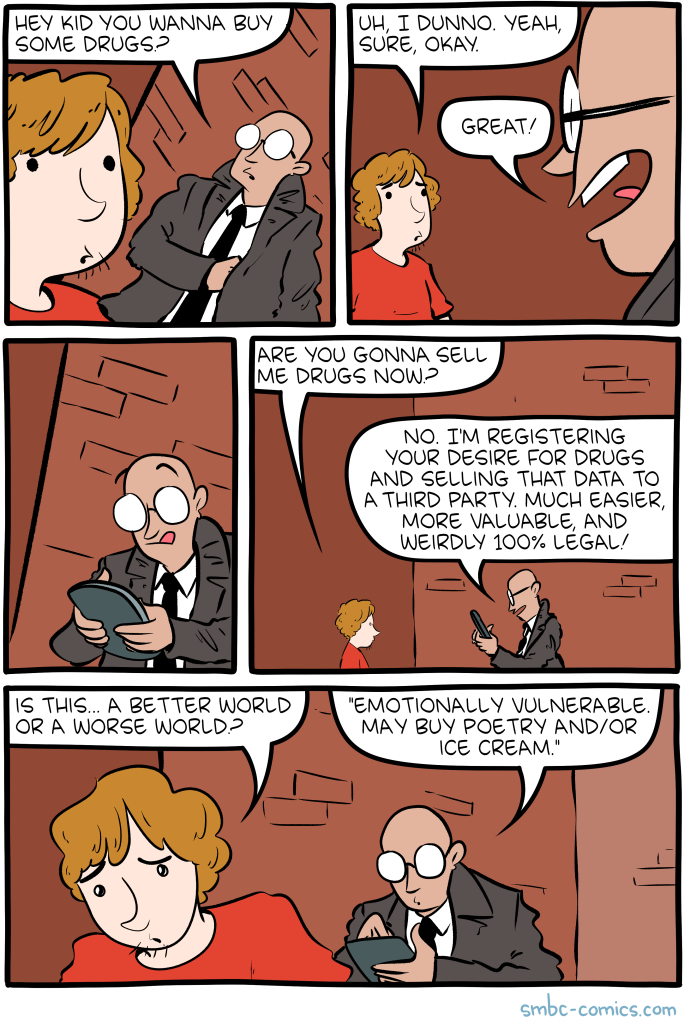

Click here to go see the bonus panel!

Hovertext:

It's not a scam if it's just 50 trillion micro-scams!

Today's News: